UPCOMING

Himmel auf Erden — Kunst. Utopie. Politik

*PEDOX-PAARE

*

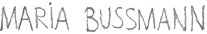

Get It White

October 27 — December 3, 2023

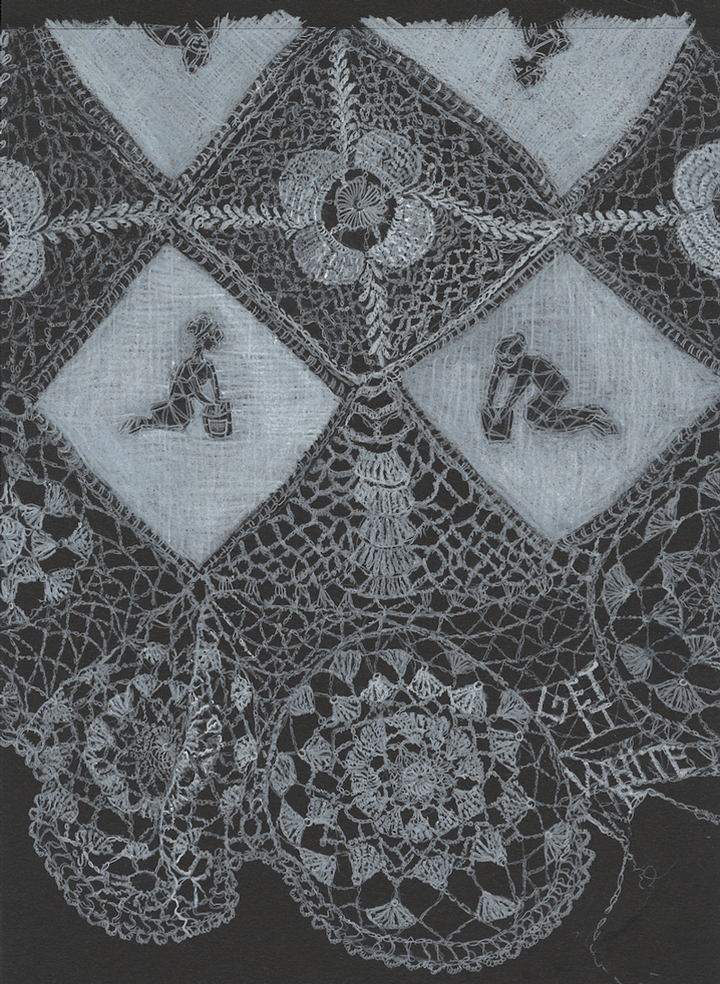

New Book

Die Debatte über Rassismus erschüttert inzwischen auch die Rezeption der Geschichte der Philosophie und trifft sie ins Mark: Gehören rassistische Strukturen zum Erbe oder gar zum Wesen der Philosophie, oder lassen sich ihre Werke unabhängig vom Vorwurf des Rassismus lesen?

Ein ungeheurer Vorwurf steht im Raum und zieht sich durch die philosophischen Debatten: Kant und Hegel seien Rassisten gewesen. Der Vorwurf kontaminiert ihre philosophischen Systeme, erschüttert ihre Prinzipien und wirft einen Schatten, der zurückreicht bis in die Philosophie der griechischen Antike. Ist es überhaupt noch möglich, die Philosophie von diesem Vorwurf zu lösen, oder müssen wir ertragen, dass der Rassismus zum Erbe ihrer Geschichte gehört? Aber wie können wir etwa Kant begegnen, wenn an seinem aufklärerischen Werk die Aufklärung bereits versagt? Und wie Hegel lesen, wenn sich seine Vernunft aus einem eurozentristischen Rassismus entfalten sollte? Und wie begegnen wir den Werken Platons und Aristoteles’? Können und dürfen wir diese Werke lesen, wenn sie kein antirassistisches Medikament verabreichen, sondern eher rassistisches Gift? Begleitet von den kommentierenden Zeichnungen Maria Bussmanns bahnt sich Sven Jürgensen einen Weg durch die hitzige Debatte. [via Passagen Verlag]

October 2023

Himmel auf Erden — Kunst. Utopie. Politik

Galerie Ernst Hilger

1010 Wien, Dorotheergasse 5

11 März 2024

*

PEDOX-PAARE

Galerie Petra Seiser, Schörfling am Attersee

Christoph Mayer und Maria Bussmann (im Kabinett)

3—27 März 2024

*

My participation in „Itinéraires Fantômes“,

a 72-card oracle deck drawn from the writings of Hélène Cixous,

(organized by L.A. based artist Alexandra Grant), curated by Marion Vasseur Raluy

and Ana Iwataki, at the CAPC Musée d'art Contemporain Bordoux, France

* Opening of the solo exhibition at FROSCH&CO, New York

Get It White

Gallery hours:

Wednesday to Sunday, 12—6 p.m.

Save the date:

November 3, Friday, 6 p.m.

discussion & book event with Maria Bussmann and philosopher Thomas E. Wartenberg

October 27 — December 3, 2023

*

New Book

Black and White are Not Colors

Sven Jürgensen, Maria Bussmann

Schwarz und Weiß sind keine Farben

Wie rassistisch ist die Philosophie?

Die Debatte über Rassismus erschüttert inzwischen auch die Rezeption der Geschichte der Philosophie und trifft sie ins Mark: Gehören rassistische Strukturen zum Erbe oder gar zum Wesen der Philosophie, oder lassen sich ihre Werke unabhängig vom Vorwurf des Rassismus lesen?

Ein ungeheurer Vorwurf steht im Raum und zieht sich durch die philosophischen Debatten: Kant und Hegel seien Rassisten gewesen. Der Vorwurf kontaminiert ihre philosophischen Systeme, erschüttert ihre Prinzipien und wirft einen Schatten, der zurückreicht bis in die Philosophie der griechischen Antike. Ist es überhaupt noch möglich, die Philosophie von diesem Vorwurf zu lösen, oder müssen wir ertragen, dass der Rassismus zum Erbe ihrer Geschichte gehört? Aber wie können wir etwa Kant begegnen, wenn an seinem aufklärerischen Werk die Aufklärung bereits versagt? Und wie Hegel lesen, wenn sich seine Vernunft aus einem eurozentristischen Rassismus entfalten sollte? Und wie begegnen wir den Werken Platons und Aristoteles’? Können und dürfen wir diese Werke lesen, wenn sie kein antirassistisches Medikament verabreichen, sondern eher rassistisches Gift? Begleitet von den kommentierenden Zeichnungen Maria Bussmanns bahnt sich Sven Jürgensen einen Weg durch die hitzige Debatte. [via Passagen Verlag]

October 2023